Source: http://www.unc.edu/depts/jomc/academics/dri/idog.html

The Internet is increasingly being used to interact with others in infinitely varied contexts and formats. I think one of the most important ways in which this occurs is the ability for internet users to now comment on news and journal articles. This can be seen to facilitate a richer form of debate with not only the original publishers able to make educated and insightful contributions. The ABC ‘s Self Service Science online forum is a fantastic example of this, where “scientists and fans of ‘sleek geek’ educator Dr Karl Kruszelnicki” collaborate to discuss events and theories and problem solve (Martin, 2012, 149).

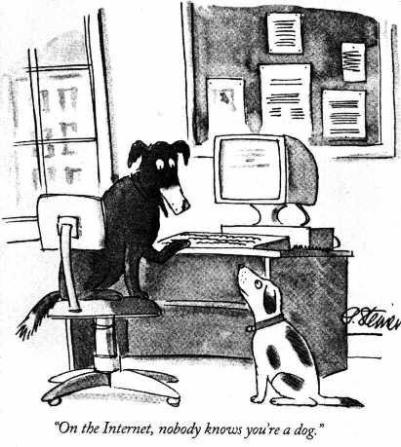

As we use the Internet more and more frequently to interact with others, questions have arisen about the ability to remain anonymous online. Anonymity allows people to comment on issues that they otherwise may not feel comfortable debating. They have the freedom to state what they believe without the fear of repercussions.

However, as Fiona Martin (2013) indicates, “we don’t, necessarily, yet have a set of inculturated responses to how we can communicate with people online.”

As such, the anonymity and “perceived disembodiment” of online communication can mean contributors are less likely to act civilly (Martin, 2012, 180). This can lead to abusive behaviours where contributors will personally offend or ‘troll’ others rather than engage in constructive debate.

Source: http://www.sodahead.com/fun/have-you-ever-really-pulled-a-gun-on-someone-besides-here-on-sodaheadlol/question-2082023/?link=ibaf&q=shhh

This type of behaviour can be seen as a silencing mechanism. People may be deterred from contributing to a discussion for fear of being abused, but also, Martin (2013) argues that negative comments can sway responses to the original event or argument. People may be less likely to engage in the original piece if they see it has already been met with a range of unfavourable responses.

Whether or not anonymity is a good thing on the Internet is difficult to judge. As Lee (2006, 7) argues, “individuals should have the right to choose how they want to communicate on the Internet.” However, I wonder if it even feasible to consider that anonymity will continue to be available to online participants?

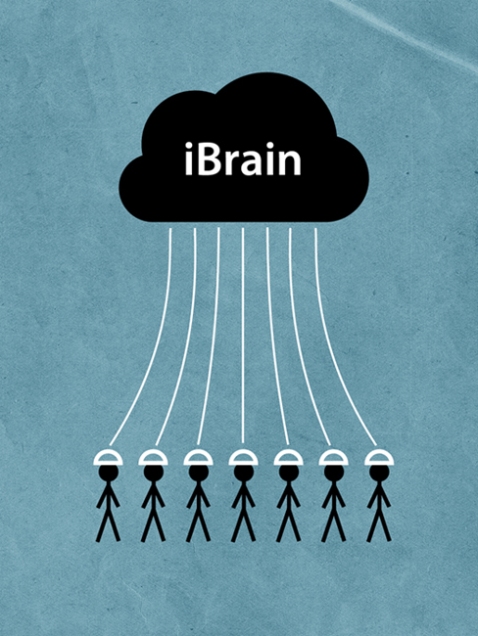

As Waters (2013) argues “most of what happens online these days is tied to making inferences about someone else’s identity.” We log onto many websites by using our Facebook details (which requires our true identity) and the use of cookies to allow websites to track our online behaviour which means that even when we don’t provide identification those websites are able to build a profile of us. Waters (2013) persuasively argues that as the ‘real’ and ‘virtual’ worlds become ever more intertwined, identity online becomes increasingly important as we need to be able to trust who, what and where we are dealing with.

Lee, Y (2006) ‘Internet and Anonymity’ Society, Vol 43, No. 4, pp 5-7

Martin, F (2012) ‘Vox Populi, Vox Dei: ABC Online and the risks of dialogic interaction’ Histories of Public Service Broadcasters on the Web, editors, N Brugger and M Burns. New York: Peter Lang, pp 177-192.

Martin, F (2013) ‘Mediating the Conversation’, BCM310, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, 20 May.

Waters, R (2013) ‘Inside Business: Online anonymity to be confined to virtual history’ Financial Times, accessed 24 May 2013, <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/5bf712b4-b281-11e2-a388-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2U9m5tTMJ >